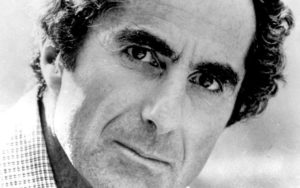

My first Roth book was Portnoy’s Complaint, which I read as a teenager. It blew my mind because I’d never read a first person narrative that was so anarchic. As Roth has written: “Nobody expects a Jew to go crazy in public.” It was also wickedly funny, and broke many other taboos. Nothing I read for school came even close to being so alive–and so entertaining. The book changed American literature forever, as the Washington Post reported today.

It hit home for me. The over-protectiveness as well as the carping of Alexander Portnoy’s parents reminded me of my own mother and father who sometimes said things just as diminishing and weird. And his rage against anti-Semitism was revelatory. But it would be awhile before I found the courage to write freely about being Jewish, the son of Holocaust survivors, and gay.

Soon after college, I read The Ghost Writer. I was in love with Henry James at the time and it seemed very Jamesian, like one of the Master’s tales about the “madness of art”–with a Holocaust twist. I read it over and over. The prose struck me as perfect, the story profound, and I thought that if I could someday write a book even half that beautiful, I would have really accomplished something fine.

I did a report on Portnoy’s Complaint in graduate school which had the seminar in hysterics because I read sections of the book aloud. It taught me something about writing as performance which I would utilize years later on my many book tours. I followed his work almost religiously, reading his criticism as well as his fiction, and the anger of his critics in the Jewish community sobered me. My first book, which combined Jewish and gay themes, got some savage reviews in the Jewish press, though nothing as bad or as widespread as Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus.

Years later, my memoir about coming terms with Germany as a son of Holocaust survivors was basically ignored by the Jewish press, including publications that had published my short stories and essays. I was relieved in a way. I didn’t have the skill to skewer critics the way Roth did, and I would not have relished a firestorm. It was bad enough that when I spoke about that memoir at a famous Jewish venue, I was attacked by members of the audience for saying anything remotely positive about my experiences in Germany. My favorite angry comment, which seems right out of a Zuckerman novel: “Okay, so you’ve been to Germany, why go back? There aren’t other countries in the world?”

Before I became a regular reviewer for the Detroit Free Press, I was asked to review his memoir Patrimony and I declined. I felt too humbled by the power and precision of his work. Now I’m sorry that I didn’t at least try.

I met Roth when he spoke at Michigan State University. He seemed bored by the questions from the audience, including mine, and when I had him sign one of his books afterwards, he was as aloof as if the experience pained him. I’d given him one of my own books with a Roth quote written above my signature and he seemed startled, “Did I really write that?”

It was a chilly interaction, but that didn’t stop me from reading and enjoying later novels, and assigning his work in a Jewish-American literature class whose students loved The Plot against America. And I’m proud to say that an essay of mine appeared in a collection where he was one of the star contributors. Better still, a reviewer in the Washington Post compared my novel The German Money to Roth (and Kafka!).

I haven’t uniformly admired all his books, but he’s still a model for me of dedication, insight, and perseverance–and his dialogue is some of the best any contemporary American author has written. Along with James, D.H. Lawrence, Anita Brookner, Fitzgerald, Edith Wharton, he’s been an abiding, inspiring presence in my life as a writer.

As Dwight Garner puts it so well in the New York Times, “His work had more rage, more wit, more lust, more talk, more crosscurrents of thought and emotion, more turning over of the universals of existence….than any writer of his time.”

Lev Raphael is the author of 25 books in many genres, including the historical novel Rosedale in Love (The House of Mirth Revisited). He’s been teaching creative writing at Michigan State University and you can study with him online at writewithoutborders.com