Edith Wharton is often on my mind, and not just this week, which saw her 156th birthday.

I fell in love with Edith Wharton’s novels and short stories in college, given that I grew up in Gilded Age New York. The building on upper Broadway I was raised in was one of two massive apartment blocks built circa 1900 by Harry Mulliken with gorgeous tapestry brickwork and stone detailing, like Mulliken’s more elaborate Lucerne Hotel on 79th and Amsterdam.

The public library I visited every week was a Venetian palazzo designed by McKim, Mead, and White. It was a temple of books, a sanctuary, and a doorway to another more elegant world. Perhaps most enthralling for me as a young boy was our family’s regular bus route downtown: along Riverside Drive past one Gilded Age mansion, brownstone and apartment building after another.

The public library I visited every week was a Venetian palazzo designed by McKim, Mead, and White. It was a temple of books, a sanctuary, and a doorway to another more elegant world. Perhaps most enthralling for me as a young boy was our family’s regular bus route downtown: along Riverside Drive past one Gilded Age mansion, brownstone and apartment building after another.

The past was all around me as it might not be in other parts of New York City, and so discovering Wharton in college was like claiming part of my own history. I bought every single book of hers then available in Scribner paperbacks and read them many times, awed by her wit, her powers of description, and her sharp eye for hypocrisy and foolishness. In the summer of 1975 I read R.W. B. Lewis’s riveting Pulitzer-winning Wharton biography that launched the revival of her work, and through reading about Wharton’s life I felt even more inspired to pursue my own career as a writer.

That career of publishing in many genres has led me back to Wharton three times. In the early 90s I published a study of the emotion of shame in her writing and her life, something that had never been discussed before. A few years after Edith Wharton’s Prisoners of Shame, I invented two fictional Wharton societies and pitted them against each other in an academic mystery, The Edith Wharton Murders.

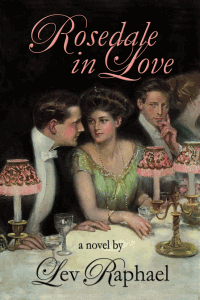

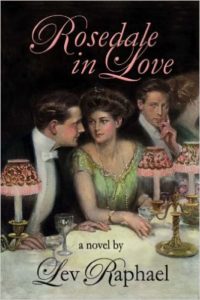

More recently, I re-entered her world in a whole new way. Undoing Wharton’s anti-Semitic stereotyping, I’ve re-imagined The House of Mirth from the point of view of Lily Bart’s suitor Simon Rosedale, giving him a home, a family, a history, and a tormented heart. In writing Rosedale in Love, I haven’t tried to imitate Wharton’s style, but I have written the book in a period voice, after immersing myself in writings of all kinds from the early 1900s.

I don’t know how she would have felt about my novel, but for me, it’s been one of the most exhilarating adventures of my writing career.

I don’t know how she would have felt about my novel, but for me, it’s been one of the most exhilarating adventures of my writing career.

Lev Raphael is the author of 26 books in genres from memoir to mystery. After close to twenty years of teaching at the university level, he now offers creative writing workshops online at writewithoutborders.com.