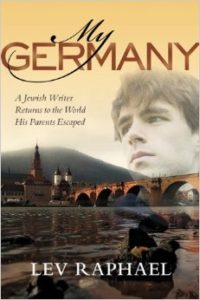

I grew up with adversity. My parents emigrated to the U.S. from Europe with very little money and weren’t helped nearly enough by relatives. Their early years in the U.S. were very hard. But this cloud hanging over us was nothing compared to the nightmarish storms they had survived in the Holocaust. I knew bits and pieces of what happened to them while I was growing up, and learned more when I became a writer and paid homage to them in a memoir, My Germany.

My mother and her family attempted to escape their Polish city into Russia in the summer of 1941 when the Nazis sent millions of murderous troops into Poland and the Baltic countries. It was the very last train, but inside the Russian border they were thrown off because they were Jews. Her father was eventually murdered by the Nazis, her mother murdered in a concentration camp, and she survived a ghetto and several concentration camps.

My Czechoslovak father was forced into the Hungarian army as a slave laborer on the Eastern Front with other healthy young Jews and was subject ed to sadistic treatment by the officers. One beating left him close to death. He still bears shrapnel in his body from when he dodged a hand grenade thrown right at him. The grenade killed his best friend. His stories of survival are something out of a thriller.

Nothing in my own life could have possibly matched the adversity they faced for years during the war, yet their survival buoyed me up through many dark times in my career as an author. Being a writer is the kind of career where success is fleeting and failure is always around the corner–and sometimes it’s so huge it’s stupefying.

When a new website for book lovers invited me to choose a topic and list five books that exemplified it, “conquering adversity” sprung immediately to mind as the organizing theme. The books I chose with my writing partner are from different genres and feature wildly different people, from Winston Churchill to a Black maid in the South, but they all have that theme and are meant to inspire readers to never give up: https://shepherd.com/best-books/conquering-adversity.

Whatever adverse situations you’re facing, I hope these five books we picked speak to you and give you courage and hope.

Lev Raphael has reviewed books for The Washington Post, The Detroit Free Press, Huffington Post, Bibliobuffet and other publications as well as three Michigan radio stations.

(free image from Pixabay)

![[cover]](https://www.levraphael.com/images/cover_mygermany_152.jpg)