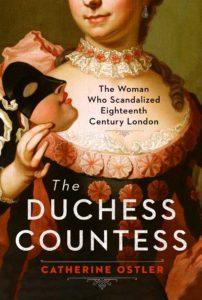

According to the author of this fascinating biography, the three most talked-about women in the 18th century were Catherine the Great, Marie Antoinette and Elizabeth Chudleigh.

Who was she? A luxury-loving, experience-hungry Englishwoman who was dubbed the “Duchess-Countess” because of having married a duke and an earl. Rising “from obscure West Country gentry” and though her finances were sometimes uncertain, she eventually moved in the highest circles of London society, was a royal maid of honor–and a bigamist.

Though her impulsive and rocky first marriage was mostly a marriage in name only, it was never legally ended when she married one of England’s richest men, The Duke of Kingston. She eventually stood trial for bigamy, complicated by complex legal maneuvering over what she inherited from her second husband. Where there’s a will, there’s a fray. . . .

Chudleigh’s bigamy trial when she was in her fifties was an international sensation and in England it even overshadowed the growing war with the colonies. As described in vivid detail, it had all the ceremony and magnetism of a coronation, given how rare it was for a peeress to be on trial in Parliament. One newspaper reported “Imagination can hardy picture a more solemn, august, and at the same time brilliant appearance, than the court in Westminster Hall.” That trial wasn’t the end of her legal troubles, and readers will be fascinated by them as well as by her taking root in Russia of all places–for a while anyway.

The book offers dazzling and sometimes bizarre insight into a world of stupefying luxury: weird do’s and don’t for those who served royalty, mammoth dinners for a cast of thousands, lavish country and city homes decorated at an unbelievable cost, clothes and jewels worth millions. It was all part of a highly rarefied lifestyle as decorous on the surface as a minuet, but treacherous if one made a misstep.

In 18th century England, Elizabeth Chudleigh almost always managed to dance that real and figurative dance with envious grace, style, and panache. She wasn’t just beautiful and decorative: she was smart, educated, multilingual, charming, a wonderful conversationalist, intensely charismatic. And as famous and controversial as any Kardashian today.

It’s too bad nobody recorded her conversation the way Boswell preserved Samuel Johnson’s bon mots and observations to make them a part of history. We hear her letters crying for help at various points but don’t get to hear her at her most relaxed and impressive.

She was a woman of great appetites, loved commissioning new homes, loved doing a Grand Tour in Europe when that was still a man’s prerogative. She was way ahead of her time in making sure she had good publicity–or trying to. And of course the brightness of her star earned her plenty of detractors and even enemies. Some of the best moments in this book are the sour comments about her in letters and diaries–you almost feel you’re reading trolls on a Twitter feed. Their criticism is often sexist but sometimes legitimate as she was impetuous, impulsive and her plans sometimes led to “drama and debacle.”

At one point when she fled England for Rome, where the pope was a supporter, “as far as the locals were concerned, the voluptuous, peculiar, emotional Elizabeth was…a one-woman carnival.” Her travels here and there across Europe, especially when she was ill, are sometimes beyond belief and the author milks them for every juicy detail.

The book is so filled with so much richness, however, that at times you might feel overwhelmed by names, banquets, vendettas, scandals, legal actions, and above all titles of nobility. It also seems a stretch for the author to keep speculating about whether Chudleigh suffered from borderline personality.

Duchess and Countess Elizabeth Chudleigh lived amazingly large, had amazing adventures, misadventures, famous friends and allies–and famous detractors. She was a figure of admiration and emulation, and the focus of a unique trial. This bountiful biography is the perfect material for a miniseries–not least for the grotesque Dickensian frenzy that erupted when Chudleigh died in Paris right before the French Revolution.

Lev Raphael’s first love as an English major was literature of the 18th century. He is the author of twenty-seven books in many genres and has taught creative writing at Michigan State University where his literary papers were purchased by Special Archives at MSU’s library.