Marjorie Taylor Greene is at it again, comparing mask mandates in the pandemic to being a Jew in Germany headed off to the gas chambers. I wonder if her dismal understanding of the Holocaust is based on reading bad novels like Kate Breslin’s For Such a Time which features a bizarre romance between a Nazi and his Jewish prisoner. Breslin’s attempts to root the book in the Holocaust are clumsy at best and her knowledge of Judaism and Jewish culture is way off. The book’s editor also seems to have been AWOL.

Examples abound. Why does she use the word Hakenkreuz rather than Swastika? The latter word is one most readers would be familiar with. Hakenkreuz is a feeble attempt to make the book feel historically accurate. So is using Sturmabteilung rather than SA or Brownshirts. Both of those are much more familiar to readers of historical novels or thrillers set in Nazi Germany–and more understandable.

Why field the obscure word Gänsebraten when “roast goose” would do just as well? Surely anyone picking up this book will understand after the first few pages that it’s set in Germany. Breslin doesn’t need to keep reminding us, as when she substitutes the word Kaffee for coffee over half a dozen times. But Kaffee isn’t italicized, which it should be since it’s in a foreign language. Page after page, you feel she’s just overdoing it and the publisher is careless and clueless.

That’s unfortunate, given Breslin’s weak grasp of German and Germany’s history with Jews. Breslin’s heroine is addressed as “Jude.” That’s the masculine for Jew in German, not the feminine, which is Jüdin. But more egregious than that, the Nazis had many terms of abuse for Jews, and simply calling her a Jew is not pejorative enough–given the period.

Breslin’s understanding of Jewish culture and religion is also grossly off-base. In a glossary at the book’s end, she defines a yarmulke as a “prayer cap.” No it isn’t. It’s a skullcap that’s not just worn at prayers by observant Jews. More incorrectly, she thinks a shtetl is a “small town or ghetto.” That’s flat-out wrong. It’s the Yiddish for a small Jewish or heavily Jewish village or town in Eastern Europe–not remotely the same thing as a ghetto.

If that inaccuracy isn’t enough, the glossary says that Jews in the Holocaust wore a “gold” star to identify “their Jewry.” (MTG also thinks the stars are gold).

Breslin further makes a hash of history when she says that “Sarah” was “a term that Nazis used for Jewesses.” That makes it sound like a synonym. It wasn’t. What she seems to be fumbling with is the legislation in 1938 which forced Jews with “non-Jewish” names to add “Sara” [sic] or “Israel” as middle names to their identity papers so that there could be no doubt they were Jewish. She and her publisher also seem oblivious to the fact that the word “Jewess” isn’t just dated, it’s widely considered offensive.

All these errors come from an author who claims to love the Jewish people. As the Erasure song goes, “Who Needs Love Like That?”

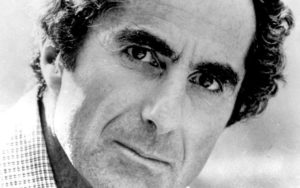

Lev Raphael is the author of 27 books in many genres including Rosedale in Love, set in New York during The Gilded Age, which is also available as an audio book.