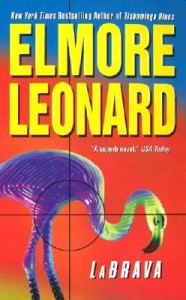

Every now and the I see people post and re-post Leonard’s well-known rules for writers. Some of them are common sense, like “Never use a verb other than ‘said’ to carry dialogue.” Taken together, though, they seem to suggest that you should write in a very lean way. Like Leonard himself.

One of the rules is “Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.” He references Steinbeck and Hemingway, but does Leonard follow his own advice? Below are some passages about the thug Richard Nobles in the novel LaBrava (aren’t those great character names?)

One of the rules is “Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.” He references Steinbeck and Hemingway, but does Leonard follow his own advice? Below are some passages about the thug Richard Nobles in the novel LaBrava (aren’t those great character names?)

He was thick all over, heavily muscled, going at least six-three, two-thirty. Blond hair with a greenish tint in the floodlight: the hair uncombed, clots of it lying straight back on his head without a part, like he’d been swimming earlier and had raked it back with his fingers. The guy wasn’t young up close. Mid-thirties. But he was the kind of guy–LaBrava knew by sight, smell and instinct–who hung around bars and arm-wrestled. Homegrown jock–pumped his muscles and tested his strength when he wasn’t picking his teeth.

An ugly drunk. Look at the eyes. Ugly–used to people backing down, buying him another drink to shut him up. Look at the shoulders stretching satin, the arms on him–Jesus–hands that looked like they could pound fence posts.

Nobles, with his size, his golden hair, his desire to break and injure, his air of muscular confidence, was fascinating to watch. A swamp creature on the loose.

I see plenty of rich, evocative detail there, and it’s all well-chosen. We get bits and pieces of the physical that create Nobles as an individual who’s anything but noble. We also see him as a type known to LaBrava who’s assessing him, and the images are powerful (swamp creature, pounding fence posts). Better yet, we have an evocative portrait of Nobles’s impact on people, the violent aura created by his mood and by his muscles.

I see plenty of rich, evocative detail there, and it’s all well-chosen. We get bits and pieces of the physical that create Nobles as an individual who’s anything but noble. We also see him as a type known to LaBrava who’s assessing him, and the images are powerful (swamp creature, pounding fence posts). Better yet, we have an evocative portrait of Nobles’s impact on people, the violent aura created by his mood and by his muscles.

Lean? Not really.

It’s easy to quote Leonard, but it’s far more interesting to read him and see how closely he sticks to his own rules. One question is, does it matter? Another, the more important one is this: why should what works for Leonard–or what he implied worked for him–work for you?

I think in the end you can learn a lot more about writing from reading Leonard’s books than reading and slavishly following his Rules. It’s also more fun.

Lev Raphael is the author of 25 books including Writer’s Block is Bunk.