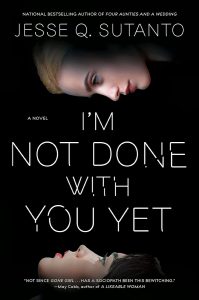

★★★★

Meet wildly paranoid and sociopathic Jane Morgan. She’s a midlist author with a dismal career; an obnoxiously superior, unsupportive husband; and a deep wellspring of jealousy and rage. Being half-Asian has always been a source of shame for her because her family is poor and she’s not slim, glamorous, and beautiful. She thinks she deserves to be one of those Crazy Rich Asians.

She hates herself as “wildly mediocre,” hates that husband, her career, social media influencers, successful writers, and especially hates California where she grew up because it’s the worst place in the world for someone antisocial like her:

“It’s too loud, too sunny, too fucking friendly. Everyone gets revved up on kale smoothies and cocaine so I can’t even get a tub of hummus without the Trader Joe’s checkout lady grinning at me and calling me honey and asking me how I’m doing and what are my plans for the weekend? Californians just can’t help themselves. If I stayed there any longer I was bound to kill someone.”

Jane’s rancid, roiling sarcasm doesn’t simply cut with a razor throughout the book, it wields an axe–and that’s perversely entertaining in this dynamic thriller.

When Jane did her creative writing masters at Oxford University, she became obsessed with Thalia, a gorgeous, charismatic, and wealthy woman in the same program. Thalia seemed to like her, which astounded Jane. Their lives mesh in reality and fantasy as the book goes back in forth in time, taking readers deeper into Jane’s pathologies.

Sutanto has a superb ear. She’s given Jane a dazzling, dark, compelling, sometimes appalling/sometimes hilarious voice of a woman trapped inside her own head who hesitates at the simplest reply because she has to make sure that it sounds “normal.” After all, she thinks that her “thoughts are spiders waiting to leap from my tongue and poison everything they touch.” And they’re worse than that since she often thinks of stabbing people just to shut them up.

She can also imagine walking through a museum “with a little razor, casually slicing apart priceless canvases” because “there’s just something about perfection that makes [her] want to defile it.” Plain Jane is a ferocious savage inside. Does Thalia tame her?

Some readers might find the multiple plot twists in the final chapters excessive. All the same, Jane and Thalia’s story is a cunning exploration of hero worship, shame, internalized racism, and the splendors and miseries of female friendship. On top of everything else, it’s a sharp and knowing satire of publishing: “Anyone who thinks that publishing is a meritocracy is not in publishing.”

Lev Raphael is the former crime fiction reviewer for The Detroit Free Press and has reviewed for The Washington Post as well as several Michigan radio stations, one of which aired his interview show. His guests there included Doris Kearns Goodwin, Salman Rushdie, Julian Barnes, and Erica Jong.