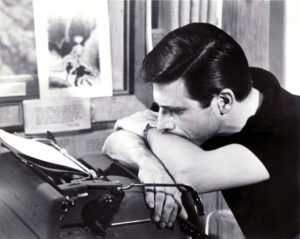

Lately I’ve been feeling like writing is a bloody battlefield — not for me, but for tens of thousands of writers across the Internet.

I’m talking about writers who seem frantic or depressed because they’re not writing fast enough every single day, as if they should be queen bees in a hive squeezing out their quota of eggs and the hive might collapse if they didn’t keep producing.

I read cries for help on social media from writers begging someone, anyone, to offer ways they can write more than 500 words a day, as if 500 words a day isn’t enough. And then I read jaunty, triumphant posts on those same platform from writers bragging about writing several thousand words a day.

The writing world in America is infected with its own special virus. The sensible suggestion that beginning writers should try to write something daily to get themselves in the habit has seemingly become interpreted as a diktat for all writers all the time. What we write doesn’t matter, it’s how much we write every single day, as if our careers — no, our lives — depended on it. As if we’re the American war machine in 1943 determined to churn out more tanks, planes, and guns than Nazi Germany because the fate of the world is at stake.

I was mentored as a writer in a time when quality not quantity was the standard and I’m happy that’s the case, because yesterday I probably wrote fewer than a hundred words. But they were crucial words because they completely re-shaped the first chapter of the sequel I’m writing to my dark novella The Vampyre of Gotham set in 1910 Gilded Age New York.

I hadn’t written anything at all for a few days before that: I was just puzzling over what needed to be done before I was ready to return to my PC. If I don’t write anything more this week, that’s fine because what I did was exactly what was necessary for the new book to move forward. And I know, anyway, that I’m writing subconsciously now that I worked out the kink in my story line. Writing happens to writers all the time, everywhere: we don’t need tablets, laptops, pens or pencils.

And we don’t need to be driven by false quotas or to feel shame because somebody, somewhere is writing a short story every week (or maybe two!) and some weeks we can barely manage to piece together a decent metaphor.

There’s nothing wrong with having a daily goal if that works for you as a writer, but why should you feel crazed because you don’t reach that daily goal — what’s the sense in that? Why have we let the word count bully us and make us feel like miserable?

Lev Raphael is the author of 26 books in genres from memoir to mystery and his fiction and creative nonfiction has been taught on college campuses across the country. With twenty years of teaching experience, he now offers mentoring, tailored workshops, and editing at writewithoutborders.com.

Photo credit:madamepsychosis