“Writers should not attack their peers.”

That’s what a famous author I deeply admired told me near the start of my career, and what he meant was personal attacks. He’d made that mistake and it launched a feud that lasted years.

I’ve been careful in my career not say much in public when fans ask me what I think about fellow authors if they’re not my favorite writers. If I do express an opinion, I keep the comments to something technical. So I might focus on their most recent book and say I wasn’t convinced by the point of view if that’s one of the problems I saw, of course. I don’t make things up.

Even after a reading at a reception or a restaurant when things are more relaxed, I’m cautious, because whatever you say may travel much further than you expect and end up making you look bad. And what you say can end up on Twitter in seconds. That’s what my mentor was trying to explain to me well before social media created firestorms. He regretted disparaging another author personally because it made him look bad and they became enemies.

I saw something similar happen in my own career, though without the feud. A celebrated American author I’d never met and who had never insulted me in the U.S. apparently decided to mock me personally in an interview in a foreign magazine when he was on tour in Europe. He didn’t know the freelancer he was talking to was an acquaintance of mine who reported the incident in detail, with some scathing comments about the author who should have known better.

Feuds come and go in American fiction, and some of them raise questions of literary taste, commercial vs. literary fiction, sexism among reviewers, but what about rudeness and bad taste? Jonathan Franzen has been a lightning rod because critics have praised him so highly. Is that his fault? Best-selling author Jodi Picoult has dismissed him as nothing but a “literary darling,” ditto Jennifer Weiner who’s done so while publicly reveled in her wealth and mocking those at The New York Times who’ve ignored her as balding (a “hairist” remark if ever there was one). Whatever the legitimacy of their complaints, should authors be engaging in this kind of snark? I guess the mockery had an impact because Weiner eventually became a contributing opinion writer at the Times….

But authors let loose on reviewers too. Franzen himself has outdone them when he attacked Michiko Kakutani a few years ago after she panned his last book, calling her “the stupidest person in New York.” And Alice Hoffman attacked the Boston Globe reviewer who gave her novel a mixed review, actually asking her followers on Twitter to call this reviewer and express their outrage. None of this makes authors look good, no matter who the target is.

A writer friend of mine was once banging out a rebuke to a reviewer when his wife came up behind him and read what was on his Mac screen. “Do you want to be respected for your work,” she asked, “or have people think you’re an asshole?”

It’s a question every author should consider when getting ready to light into a peer. It’s one thing to talk about the work, another to diss the writer.

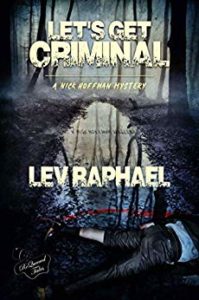

Lev Raphael’s 27th book is the mystery Department of Death which Publishers Weekly called “immensely enjoyable” in a starred review.

(free image from Pixabay)