Essays, stories, and books of mine have been taught at colleges and universities around the country, so I’ve been invited to speak at many different institutions over the years, from Ivy League schools to community colleges.

They’ve all had something in common. Invariably, a faculty member will take me aside during my time there and tell me about somebody wildly eccentric or even out-of-control in their department. Or about a scandal, a schism, some long-simmering vendetta. And I think to myself, “You can’t make this stuff up…”

There was a professor who told me she had to quit serving on hiring committees because a senior professor announced that he didn’t like a candidate because “He smells.” Nobody else had noticed anything (not that it should have mattered) but they yielded to the professor’s seniority. Another related the story of a professor who unexpectedly and savagely attacked his own student at the student’s doctoral defense just to undermine a rival professor on the committee who liked his student. Crazy, right?

I’ve heard of people with barely any publications get tenure through favoritism and then when they achieved their ultimate goal of becoming administrators, they become petty, smiling dictators over faculty with far more experience and reputation. There’s constant infighting, piss-poor collegiality—but worst of all, the sad stories of contemptuous professors who treat their students like dirt. And lately, of course, stories of sexual harassment and abuse have darkened the picture.

I love teaching and come from a family of teachers. I left academia after over a decade of teaching because I wanted to write full-time, and my editor at St. Martin’s Press encouraged me to start a mystery series set in that environment. Outsiders slam academia for not being “the real world,” but I disagree 100%.

At times it’s far too real and so are many of its denizens: petty, vain, hypocritical, self-righteous, power-hungry, wildly egotistical, obsessed with stats (perceived or real).

At times it’s far too real and so are many of its denizens: petty, vain, hypocritical, self-righteous, power-hungry, wildly egotistical, obsessed with stats (perceived or real).

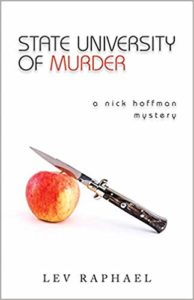

I set my series at the fictional State University of Michigan in “Michiganapolis” somewhere in mid-Michigan. Outsiders can make great observers and sleuths, so my sleuth Nick Hoffman is primarily a composition teacher there. That’s made him low man on the totem pole in his Department of English, American Studies, and Rhetoric—especially since he enjoys teaching this basic course. He’s even more of an outsider because he’s published something useful, a bibliography of Edith Wharton, as opposed to a recondite work of criticism only a few dozen people might read or understand. On top of all that, he’s from the East Coast, he’s Jewish in a mostly Gentile department, and he’s out.

Seven years ago, I was recruited to teach creative writing at Michigan State University when the chair of the English Department realized I’d published more books than the entire creative writing faculty put together. I’ve had amazing students to work with, known a few friendly colleagues, and most importantly, I was able to pass on the terrific mentoring I got in college. But in my years at MSU I’ve heard more stories of mistreatment, poisonous arrogance, and basic cruelty on campus and from friends teaching across the country. It’s all material, of course–but it shouldn’t have to be.

Lev Raphael teaches creative writing online at writewithoutborders.com. He’s the author of 26 books in a wide range of genres including the just-published State University of Murder.