Back when I was still teaching creative writing at Michigan State University, a senior colleague at Michigan State University’s English Department asked if I wanted to join him to start a summer abroad program in Sweden. I didn’t hesitate. I’d been watching Swedish movies and reading Swedish mysteries for years.

The program was going to be housed at historic Lund University in the south of that country not far from Copenhagen, and I plunged into reading everything I could about the region, its culture, history, sites, and food. More than that, I began studying Swedish, which would be my third foreign language after French and German.

I fell in love with both the sound and sense of it. Swedish has multiple stresses in it which makes it more musical than English and German; the grammar isn’t nearly as complicated as German; the spelling is much simpler. Best of all for a beginner, in the present tense the verb form is identical in each position. You can do a lot with just the present tense.

I immersed myself in all things Swedish and learned about Fika, their afternoon coffee break with something like a cinnamon bun, and better still, their concept of lagom: being contented with having just enough, which is so antithetical to the American hunger for more, more, more.

I studied Swedish daily via Pimsleur or Babbel or Duolingo–to the point where a friend with Swedish relatives said my accent was really good. “You sound like my uncle!”

Though I’d be teaching in English, and Sweden ranks very high in Europe for English language fluency, I wanted to be able to talk to Swedes when I traveled around the country in their own language. I was busy, busy, busy.

On the academic front, I planned a creative writing course and a course in Swedish crime novels in translation. We were fired up. But my colleague and I hit a massive roadblock. Lund University insisted on having one of their professors do guest lectures at $1500 an hour and assigning us a student assistant for several thousand more. Our budget couldn’t handle those expenses and they wouldn’t negotiate. End of a dream.

When the pandemic hit and Michigan went into lock down, I found myself at loose ends and bored, since I wasn’t working on a book. I looked around for ways to structure my time when everything seemed so uncertain, and Swedish seemed a natural choice. Since March, I’ve been re-experiencing the joys and challenges of a language with some similarities to German but oh-so-many differences. Like the articles tacked onto the ends of the nouns: Hus is Swedish for house, and the house is huset.

After breakfast very morning, I have a second cup of coffee and do 10-15 minutes of Swedish On Duoling and feel as calm as if I’m meditating.

When all this is over, I would still like to travel to the south of Sweden, which is beautiful and close to Copenhagen, and see the gorgeous old college town of Lund. It’s apparently small enough to walk or bike across in less than half an hours. Lund is also close to where the Wallander mystery series was filmed as well as the larger cities of Gothenberg and Malmo. I’ve kept all my travel guides in the hope that it comes to pass.

My favorite Duolingo Swedish sentence is in the title of this blog: Jag kan inte hittar mina byxor. I would love to have the occasion to use it there to see how people react.

Lev Raphael is the author of 26 books in many genres, most recently State University of Murder.

Twitter photo credit: Jerker Andersson/imagebank.sweden.se

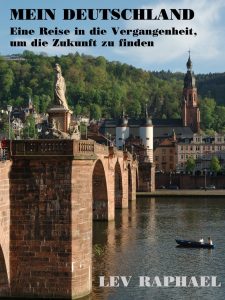

![[cover]](http://www.levraphael.com/images/cover_mygermany_152.jpg)