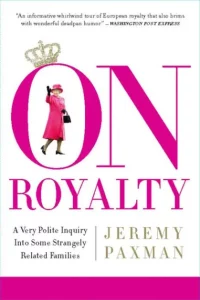

Fans of The Crown or anyone who watched Queen Elizabeth’s recent funeral will love On Royalty, an exploration of the very strange institution of monarchy across Europe. The focus by English journalist Jeremy Paxman is mainly on the world’s most prestigious and most talked about throne, the English one, but the author also explores monarchies across the continent and through the centuries.

The book is amusing, thoughtful, wide-ranging. A case in point: his account of Albania and its kings. There were advertisements in 1913 in British newspapers for a country gentlemen to become the Albanian king after various princelings in Europe were offered the position. They decline ruling the wild, mountainous little land where clans engaged in ancient vendetta. A local chieftain ended up as King Zog but abandoned the throne after a year, and a highlight of the book is the author’s interview with the current pretender to the thrown, his son King Leka, who seems utterly clueless and delusional.

What does it take to be a king or queen? Birth is the prime requisite but after that, expectations are low: being able to decently deliver a speech that’s been written for you is high on the list. Royalty across Europe seems rarely to have been particularly well-educated, with past multilingual exceptions like Queen Elizabeth I and the more recent Queen Margarethe of Denmark.

The right religion counts too, not just in terms of whom you marry. There’s a good deal of fascinating detail about Queen Elizabeth’s deep religious feeling, some of which came across deftly in The Crown.

The author has a gift for well-crafted, dramatic anecdotes; his storytelling never lags and he always offers insight and entertainment. Paxman’s analysis helps explain both the global fascination with royalty and how monarchy survives today “not by any will of its own, but by the collective delirium of its citizens.”

As Paxman says early in the book, many kinds of monarchs are accepted: “good or bad, saintly, lecherous, wise, stupid, athletic or indolent. All will be tolerated because those who believe in the hereditary principles necessarily accept that their heard of state will not be there by election, talent, or ambition. No other area of human activity is so easily reduced to three essential transactions of birth, marriage and death.”

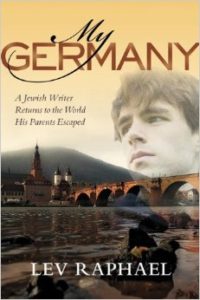

Lev Raphael is the author of 27 books in genres from memoir to mystery and has seen his work studied in university classrooms, written about by academics, discussed at academic conferences, and translated into 15 languages.

*

*

![[cover]](https://www.levraphael.com/images/cover_mygermany_152.jpg)