Chris Bohjalian’s most recent novel of suspense tells a gripping story about an alcoholic flight attendant, Cassie Bowden, who wakes up in a luxury hotel bed in Dubai next to a murdered man she slept with the night before. His throat’s been slashed and there’s lots of blood in the bed. When she drinks too much, she has blackouts, and she’s wondering if she could have killed him, though she can’t imagine why.

What should she do now?

Cassie has a history of bad choices and some of what she does immediately and in the days after her horrific discovery is truly off the wall–when it’s not just plain dumb. The lawyer who eventually tries to help her has no problem calling her crazy.

So who killed Cassie’s sexy, wealthy hook-up? And was he really a hedge fund manager? Cassie doesn’t know, but before long she starts suspecting that she’s being followed. In classic thriller style, her troubles escalate as the story unfolds, and often because of her own mistakes. Cassie is almost a total screw-up, but it’s hard not to sympathize with her, given the alcoholism in her family. And given that she’s painfully aware of how stuck she is in very bad patterns:

She wanted to be different from what she was–to be anything but what she was. But every day that grew less and less likely. Life, it seemed to her…was nothing but a narrowing of opportunities. It was a funnel.

The details of her work life in the air and on the ground are fascinating, ditto how she interacts with her fellow flight attendants, and Bohjalian is at his best describing Cassie’s shame about her alcoholic blackouts.

But the writing is a bit odd at times. Streets and aisles are described as “thin” rather than “narrow” for no apparent reason. The author has a fondness for unusual words like “gamically,” “cycloid,” “niveous,” “ineludibly,” “noctivagant,” and “fioritura” which stop you right in your tracks. The last one is a doozy. It refers to vocal ornamentation in opera and seems totally out of place in describing a lawyer’s complaint to her client.

At a point when Cassie is longing for a drink, it’s not enough for Bohjalian to call it her ambrosia. No, he has to pile on synonyms “amrita” and “essentia.” Seriously?

You get the feeling with all these splashy word choices that Bohjalian is showing off, but why would a best-selling author bother? Does he somehow feel that he has to jazz up his thriller with fancy-shmancy diction to prove that he’s more than just a genre writer?

Bohjalian also spends way too much time on Cassie’s amygdala, her “lizard” brain, and mistakenly thinks it’s a seat of reflection. It isn’t.

Almost as annoying as his vocabulary or his weak grasp of neuroscience is the fact that his American characters sound British when they use “rather” as in statements like “I rather doubt that–” Even the narrative employs “rather” as a modifier way too often. This is apparently a tic of his that nobody’s bothered to point out to him. Likewise, Bohjalian uses formal phrasing in a story that’s anything but formal, so time and again there are constructions like this one: “She hadn’t a choice.” Given the book that he’s written, “She didn’t have a choice” seems more direct and natural.

Despite the distracting quirks, I stuck with this thriller because the protagonist is a fascinating hot mess and Bohjalian is a solid story teller when he gets out of his own way. The novel has some fine twists and a satisfying and surprisingly heartwarming ending.

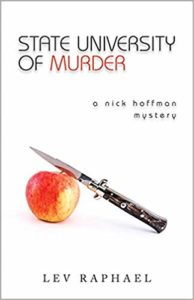

Lev Raphael is the author of 26 books in many genres including the newly-released mystery State University of Murder. He teaches creative writing workshops online at writewithoutborders.com where he also offers editing services.